Recent research from The Pirbright Institute has revealed new parts of the foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) that stimulate an immune response, which could be used to inform the design of improved vaccines. They also discovered that specific immune cells were present in cattle samples four years after the animals had been vaccinated, indicating for the first time that they play a role in long term vaccine protection.

FMD affects a large range of domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs, as well as various wildlife species, and is estimated to cost between US$6.5 and 21 billion in countries where the disease is prevalent. Effective vaccines are essential for the control of FMD but it has been difficult to determine which parts of the virus trigger robust immune responses, which is vital for informing vaccine development.

In a collaboration with the University of Miyazaki, Japan, Pirbright scientists focussed on understanding the FMD response of immune cells called T helper cells. These activate other cells in the immune system that fight FMD infection and they can ‘remember’ specific parts of FMDV, contributing to long term immunity in animals. If vaccines can be designed to trigger improved T helper cell responses, they could provide enhanced and longer lasting protection.

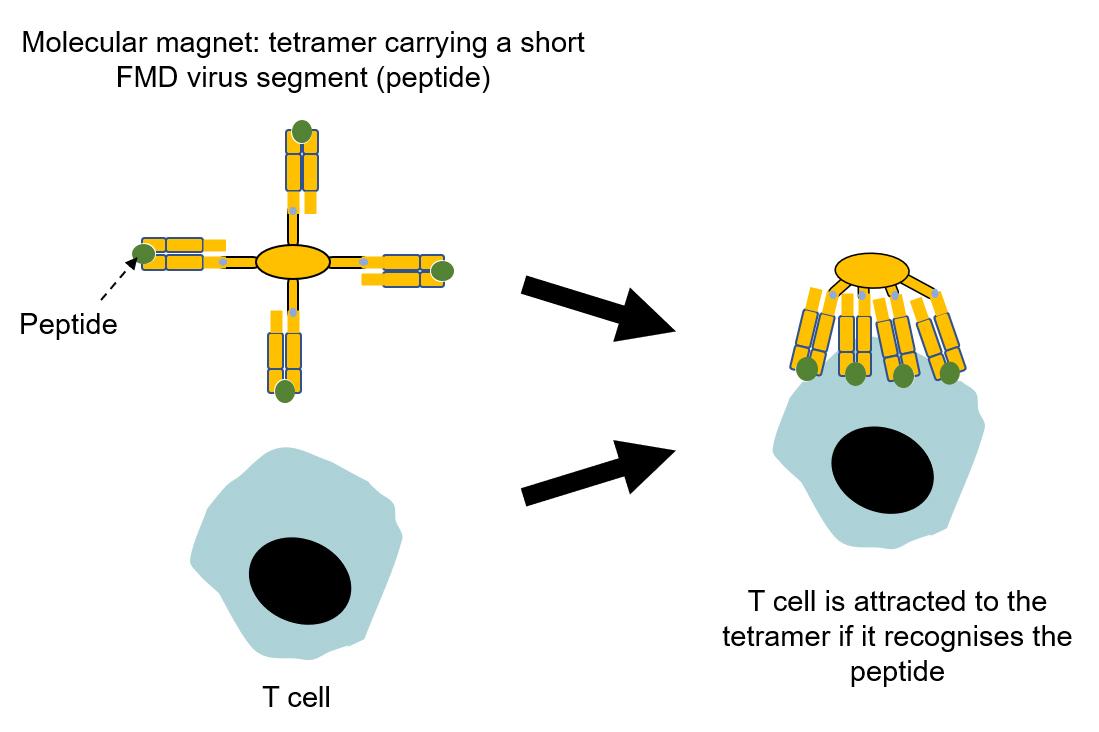

The team used man-made molecules called tetramers to establish which virus components the T helper cells responded to. Tetramers each carry a different part of the FMD virus (such as a short segment of a surface protein), which can be used like molecular magnets to ‘catch’ immune cells that recognise them. Scientists used tetramers to pick out individual immune cell types and build up a picture of which T helper cells are stimulated by different parts of the virus outer shell (known as the capsid).

Their findings, reported in Immunology, revealed four FMD virus molecules that T helper cells recognised, three of which had never been identified before. They also demonstrated that T helper cells were still present in cattle blood samples four years after the animals had been vaccinated against FMD, the first time that the life span of these cells has been studied. This finding adds to the evidence that T helper cells play an important role in long term protection following vaccination.

Dr Julian Seago, Head of the Molecular Virology group, said: “Uncovering which cells respond to each virus component would be like finding a needle in the haystack if we didn’t have the tetramer ‘magnets’ to pull them out of samples. With these tools we can really start to build up a detailed map of the FMD immune response, and we can use this to inform which virus components could be used in vaccines to generate robust and long-lasting immunity.”

This research was supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.