A new gene editing tool has been successfully applied to the southern house mosquito by researchers at The Pirbright Institute. This paves the way for genetic control methods that could prevent the mosquito from spreading human and animal diseases.

The female southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus Say) largely feeds on birds which results in the transmission of avian malaria, a key contributor to the extinction of several avian species. This mosquito species will also target mammals, spreading diseases such as lymphatic filariasis, for which there are 50 million human cases worldwide despite great efforts with mass drug administration programmes. Since the southern house mosquito’s introduction to the USA in 1999, there have also been 48,000 reported human cases of West Nile virus (WNV).

Current control strategies for the southern house mosquito are heavily dependent on the use of insecticides, but these impose hazards to both human and ecosystem health and are becoming increasingly ineffective with the rise of resistance. Advances in genome editing have allowed the development of genetic insect control methods, which could be highly effective and are species-specific.

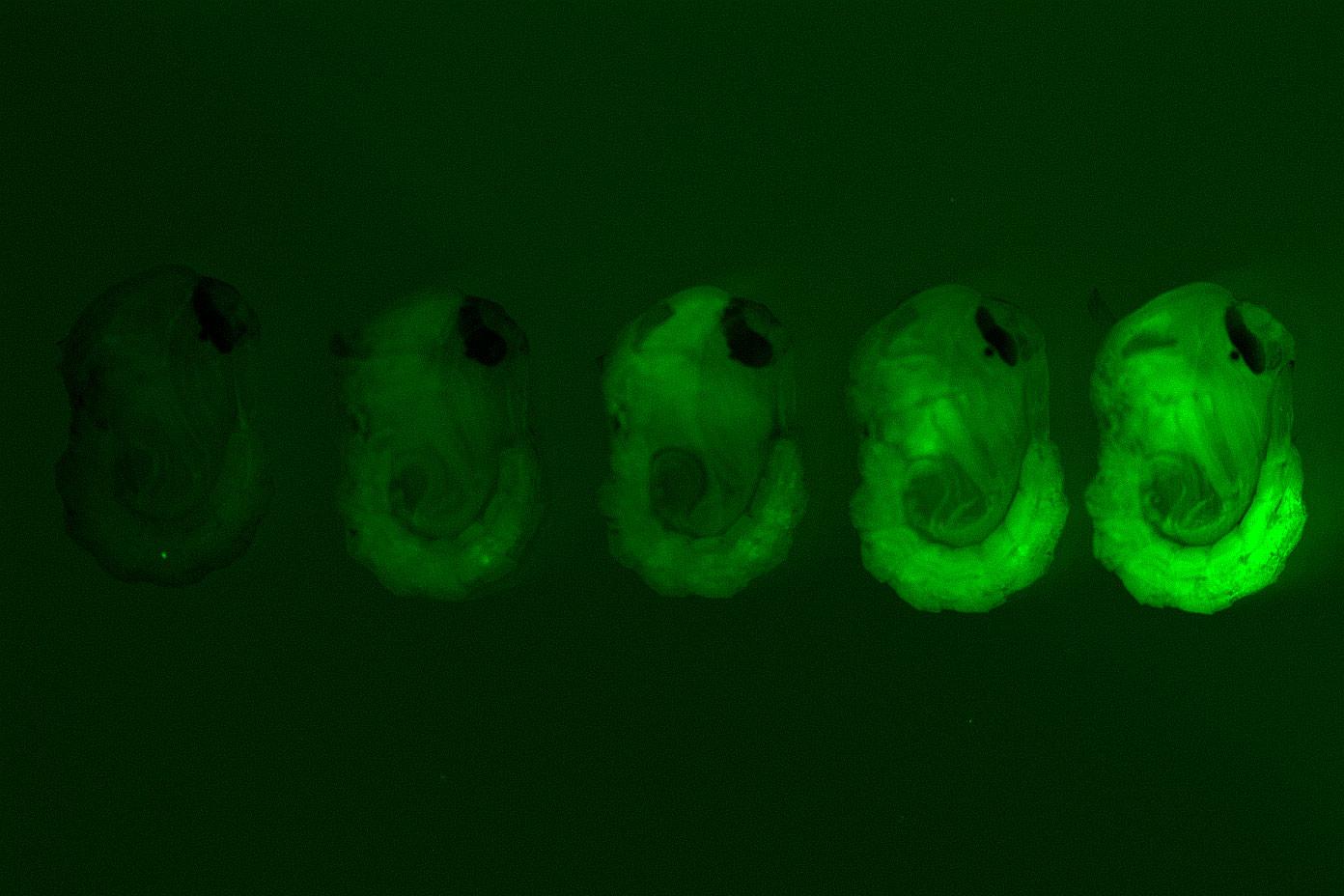

In results published in Scientific Reports, scientists showed a method that involves a gene editing tool called CRISPR/Cas9 could be used to successfully introduce a gene for a fluorescent protein into the genome of southern house mosquitoes, and that the gene could be passed on to the next generation through mating. This is a vital component of generating genetic pest management tools, as it will allow the desired traits (such as the inability to spread a disease or produce fertile offspring) to be spread throughout a population.

Culex quinquefasciatus late larvae with pigmented eyes, from bottom to top: Wildtype (WT), heterozygous for the kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (kmo) gene insert (red fluorescence, black eyes), homozygous for the kmo insert (marked by red fluorescence and white eyes)The inserted gene produces red fluorescence proteins so that mosquitoes with one or more edited gene fluoresce red. Scientists targeted an eye colour gene for the insertion site of the fluorescence gene so that mosquitoes that inherited two edited genes from their parents would have white eyes instead of black. Both these traits make it easier for scientists to easily identify mosquitoes whose genomes had been modified.

Interestingly, mosquitoes that had white eyes (which had inherited two copies of the edited gene) did not survive into adulthood. This affect is not seen when the same method has been applied in other species and highlights differences between mosquito genomes. Although this specific eye colour gene would not be targeted for creating any functional genetic pest management tools, it has provided proof that the method can work in this species.

Professor Luke Alphey, Head of the Arthropod Genetics group at Pirbright said: “Other methods for genetically engineering the southern house mosquito have been attempted, but none of them work well enough to be useful in the field. This CRISPR/Cas9 method overcomes previous difficulties and opens up a whole new avenue for scientists to generate genetic pest management strategies. This could ultimately prevent millions of people and animals from falling ill because of this invasive mosquito species.”

This research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Main image shows Culex quinquefasciatus adult females, expressing red fluorescent protein on left and wildtype (WT) on the right.