One Health Day, celebrated on 3 November each year, raises awareness around the need for research to join across many disciplines to solve the world’s critical health challenges. The One Health agenda advocates that scientists consider how animal, human and plant health are interlinked and to apply a holistic approach to tackle emerging infectious disease, antimicrobial resistance, climate change and pollution.

Scientists at The Pirbright Institute are currently working on projects that take a One Health approach to vaccine development for three zoonotic diseases (those that can spread between animals and humans): Nipah virus infection, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) and Rift Valley fever (RVF). The World Health Organization (WHO) has listed them as priority diseases to encourage research into their prevention before they become a serious global issue.

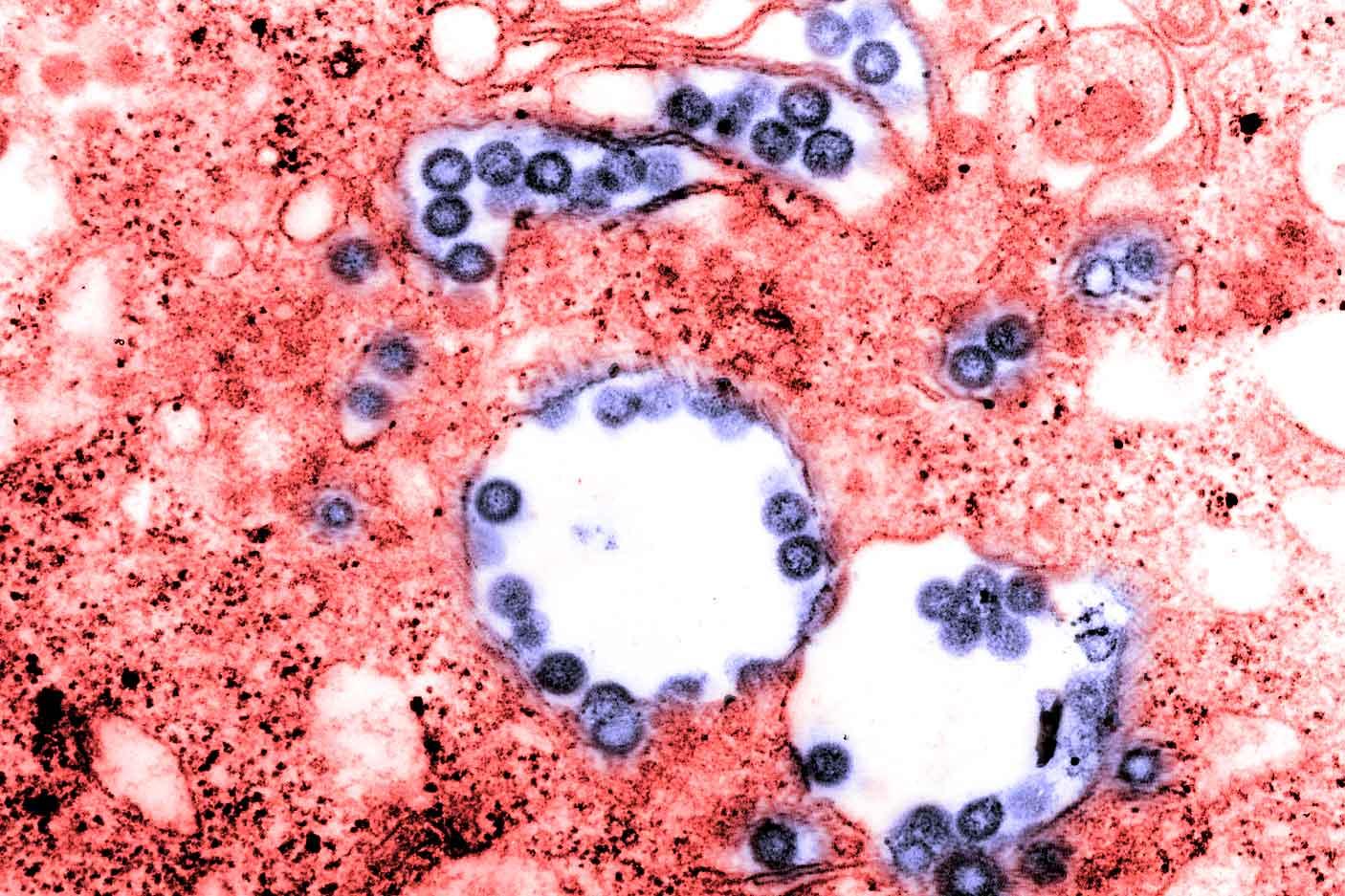

Nipah virus infection

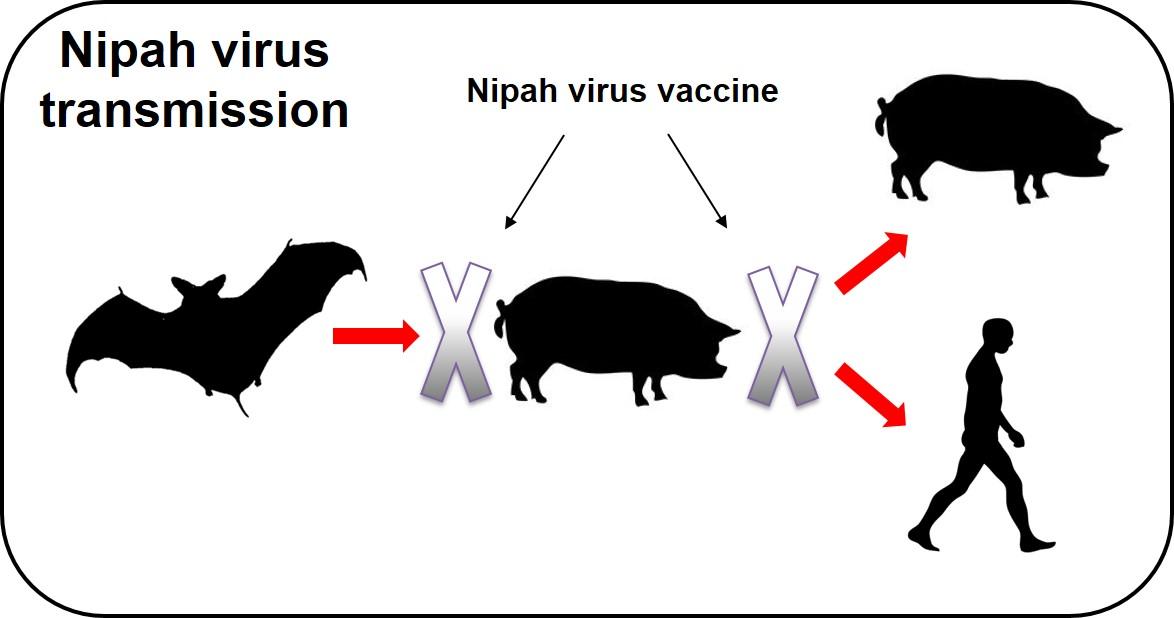

False coloured electron micrograph of Nipah virus Nipah virus is usually found in Old World fruit bats, but infection in pigs increases the likelihood of the virus transmitting to humans and causing severe, often fatal, neurological disease. It was discovered in Malaysia in 1998 and has subsequently been recognised as the cause of outbreaks in Bangladesh and India. The region at risk of Nipah virus infection has some of the highest pig population densities found anywhere in the world, which increases the risk of its transmission to pigs and humans.

Pirbright scientists are leading an international research project to create a Nipah vaccine that can give at-risk countries an alternative option to culling vast numbers of susceptible pigs during future outbreaks. The team has already shown that three candidate vaccines can protect pigs against Nipah virus infection under laboratory conditions. They are now preparing to test if protection is maintained after a single vaccination and from this information they will select a prototype vaccine to test under field conditions in Malaysia and Bangladesh.

The vaccine will prevent the cycle of transmission from bats to pigs and pigs to humans, improving animal welfare, public health and economic prosperity. Successful development of this vaccine will also provide a solid basis for further evaluating its ability to protect humans against Nipah virus infection.

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever

False coloured electron micrograph of CCHF virus CCHF infects sheep, goats and cattle without displaying any clinical signs, but if transmitted to humans it can cause severe disease, with 10-40% of cases resulting in death. To combat CCHF, Pirbright scientists have designed and led a field trial in Bulgaria to test whether a vaccine developed by Public Health England protects sheep against natural infection.

They are currently analysing over 5,000 serum samples and ticks that were collected in collaboration with regional vets from the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency (BFSA) during a six month period to gain a better understanding of the disease dynamics in the field and establish reliable estimates of the vaccine effectiveness in sheep in a high risk area.

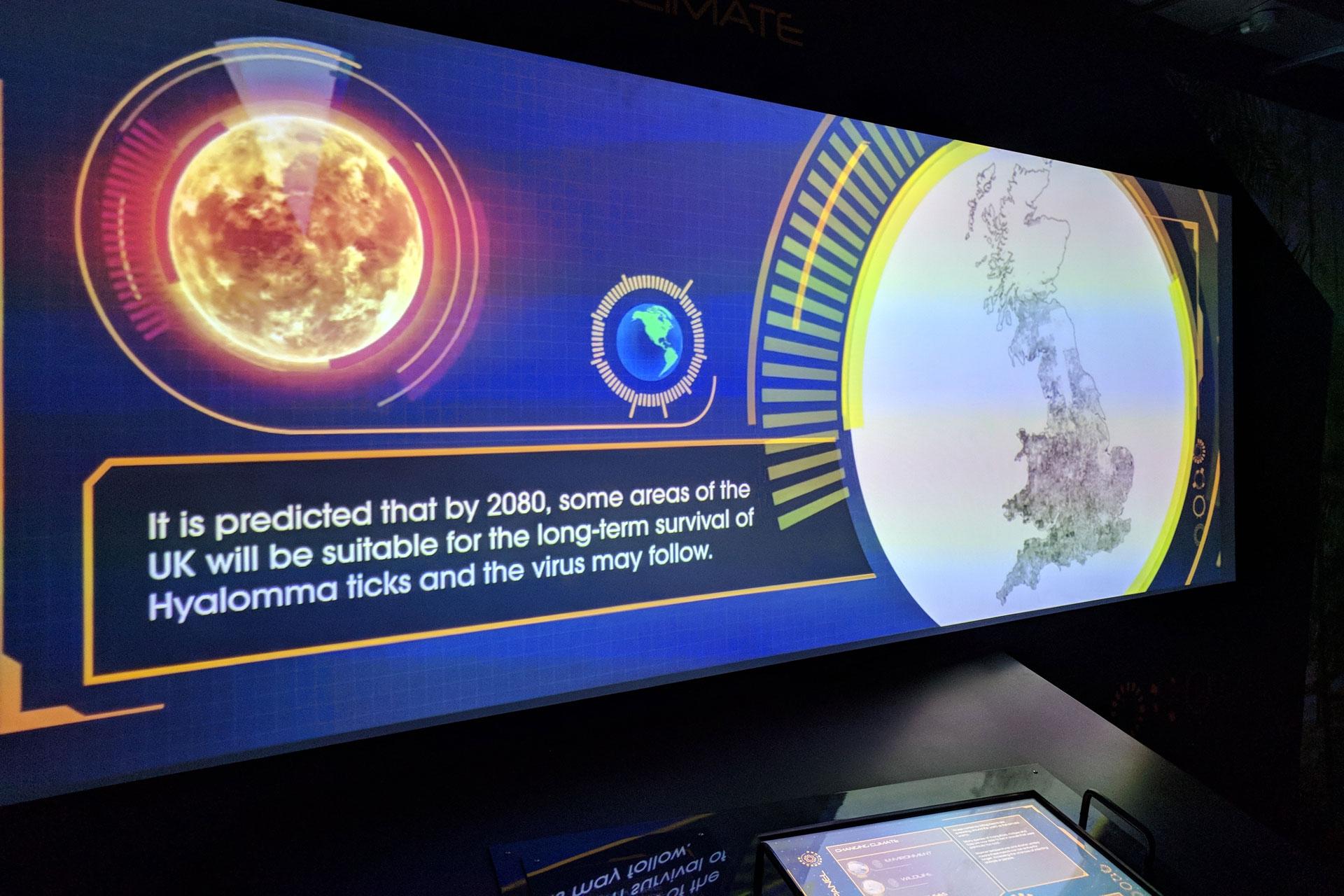

A sheep being vaccinated during the CCHF vaccine trials in BulgariaThe risk of exposure to CCHF is likely to increase due to predicted changes in the environment and agriculture, making access to effective vaccines extremely important. For example, scientists at Pirbright, together with those at Marwell Zoo, have shown that the effects of climate change may mean that the UK will become warm enough for the ticks that carry CCHF to sustain a population by 2080.

By developing vaccines to protect susceptible animals from CCHF, the risk to people can be reduced. The development of a human CCHF vaccine is the focus of PHE research and these field vaccine trials in animals will also help indicate which vaccines could eventually be used successfully in people. Phase I safety trials for vaccine use in humans are estimated to start in early 2020.

Rift Valley fever

False coloured electron micrograph of RVF virus RVF clinical signs in animals can vary in severity depending on the species, but pregnant and young animals are particularly susceptible and a lot more likely to abort their foetuses or die from infection. If passed to people through mosquito bites or contact with infected animal fluids (for example when dealing with abortions), RVF can cause mild disease with flu like symptoms. About 1-2% of patients develop a much more severe infection in which the fatality rate may be 10%–20%.

In partnership with The Jenner Institute, KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Pirbright scientists are conducting a field trial for a new RVF vaccine in Kenya. Most vaccines are currently designed separately for animals and humans, which increases development time and cost. However, the new RVF vaccine, created by The Jenner Institute, has been developed to protect both susceptible animals and humans from the disease. Pirbright scientists have recently shown that the vaccine is safe in pregnant animals, which is vital in order to ensure it can be used during outbreaks, and provides important information for human trials.

Goats in the Kenya RVF vaccine trialThe field trial has been conducted on the 33,000 acre ILRI Kapiti farm, which subjects the trial animals to the local environment including contact with wildlife species and the associated diseases they can transmit. As a non-inferiority trial, the vaccine is being compared to an already commercially available vaccine to see if it provides similar or better protection, a practice that is carried out routinely in human medicine, but rarely in veterinary studies. This is a clear example of how the One Health approach can help improve vaccine development efficiency and effectiveness.

All three vaccine projects have been funded by the Department of Health and Social Care as part of the UK Vaccine Network (UKVN), a UK Aid programme to develop vaccines for diseases with epidemic potential in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).