Studies assessing the effectiveness of anti-viral treatments for swine flu and those seeking to understand the behaviour of the virus, must factor in the route of infection during experiments, as this has a greater impact on results than previously thought, a new study from The Pirbright Institute has found.

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a global health threat. The infection in pigs causes severe disease when combined with other respiratory pathogens, and can result in considerable economic losses to farmers, and poses a significant risk to humans too.

The porcine lung has significant similarities to the human lung and as viruses of human origin also easily adapt to transmission in pigs, the pig is a useful model for scientists studying the influenza virus and for those developing anti-viral treatments, both for humans and animals.

In experiments, scientists deliver the virus to the host intra-nasally, intra-tracheally or by aerosol. However very few studies have compared the outcomes of the various methods and there have been no direct comparisons of aerosol and natural contact infection methods. An understanding of these outcomes is important in order to ensure data from experiments using the various approaches is compared accurately.

Scientists from the Institute evaluated the amount of virus shedding and the levels of immune responses from pigs following infection with a high dose and a low dose of swine flu virus (influenza A swine pH1N1) using intra-nasal and aerosol routes of administration, and compared the outcomes with pigs that had been infected through contact transmission – or the `natural` route.

The results published in Veterinary Research, indicate that the virus kinetics (the way the virus multiplies in the animal) and the immune response in naturally infected animals, differs from those of animals experimentally infected by different doses and methods.

Influenza virus A in small droplets has previously been shown to be 100 times more infectious than virus in large droplets, and the results of the Pirbright study showed that pigs can be infected with a much lower dose of virus when administered by aerosol rather than intra-nasally.

Although animals infected intra-nasally required a higher dose to establish an infection, the animals produced more virus and were better able to transmit it once infected. In contrast, those infected with a high dose of virus by aerosol, did not transmit it efficiently.

The study showed that virus administered by aerosol was more effective than intra-nasally at reaching the lower respiratory tract (LRT). This suggests that virus replicating in the LRT is better contained than virus in the upper respiratory tract (URT), and therefore less likely to be emitted, indicating that replication in the URT is the source of virus for both direct contact and airborne transmission.

Natural infection by contact was found to be the most efficient route - inducing a strong immune response (innate and adaptive), even when the animals were exposed to a very low virus dose. Such a strong response more closely resembled the immune response generated by directly inoculated animals using a high dose of virus.

Dr Elma Tchilian, group leader for swine influenza immunology at the Institute said: “Our comparison of intra-nasal, aerosol and contact infected animals shows that the route of infection and the dose of infectious virus have major effects on the outcome in terms of infectivity, viral shedding, immune response and pathology and should therefore be taken into consideration in experiments testing new vaccines or drugs.

“Furthermore, while the ‘natural’ contact route of infection may be the most effective, this approach requires the use of more animals and therefore a low dose of virus using aerosol, may be the next best alternative in such studies”.

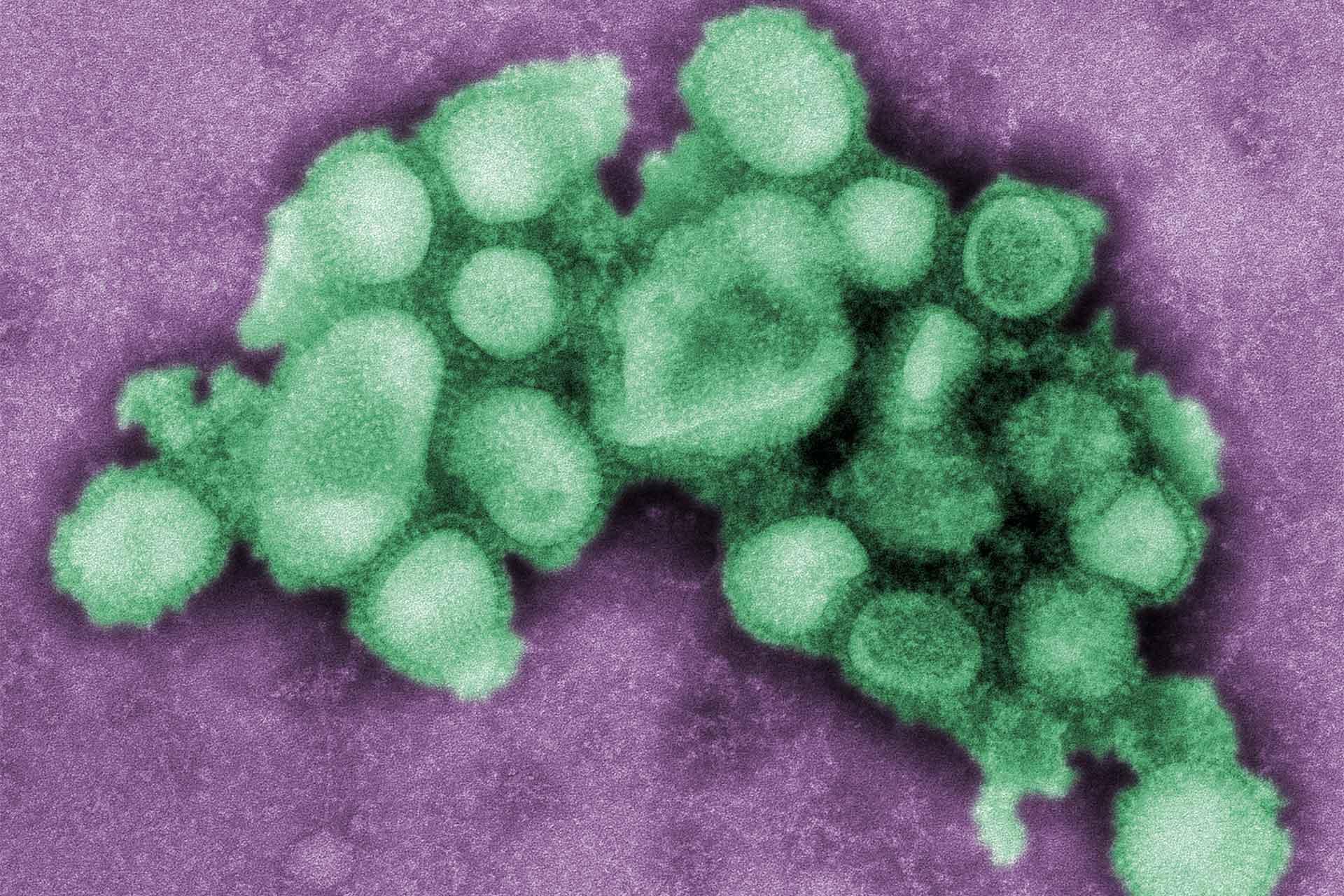

*Image by C. S. Goldsmith and A. Balish courtesy of Public Health Image Library (PHIL)