Two recent studies from The Pirbright Institute and the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute show that two vaccines against specific strains of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) do not offer complete protection against a third strain, and that this may be partly down to the temperature range the vaccine virus can survive in.

IBV is a coronavirus which causes an economically important disease that affects the respiratory systems of poultry. Commercial vaccines are currently made by passaging an infectious strain of the virus through eggs to weaken them, but the genetic changes that are made during this process are not consistent and could potentially be reversed, resulting in disease.

Recent research at Pirbright has focussed on using genetic engineering to insert the protein of a virulent IBV strain into Beaudette, a lab adapted IBV strain that doesn’t cause disease in birds. The resulting modified virus can be used in vaccines to stimulate an immune response that protects chickens against the virulent strain.

Dr Erica Bickerton, head of the Coronaviruses Group at Pirbright said: “We have previously shown that Beaudette viruses containing the spike protein of a virulent strain called M41 are able to protect chickens against M41 infection. The same goes if we follow the process for another virulent strain, 4/91. But we wanted to see if combining these two vaccines offered what is known as cross protection, where the vaccines can protect against a completely different strain called QX.”

In their recent paper, published in Vaccines, the team collaborated with researchers at the Roslin Institute to demonstrate that administering the two vaccines to chickens in varying orders reduced the levels of QX in different locations. Although signs of disease were also reduced, the two vaccines were unable to offer the birds complete protection against QX.

The researchers noted that the Beaudette vaccines did not replicate effectively in chickens, and that low levels of the vaccine virus could be one of the reasons for inadequate protection. “The Beaudette strain is highly adapted to lab conditions, where we study the virus in cell cultures kept at 37°C. But chickens have a core temperature of about 41°C, so we started investigating whether the Beaudette strain was able to replicate at these higher temperatures”, Dr Bickerton explained.

In a follow up paper, published in Viruses they revealed that the Beaudette strain could replicate in the beak, where temperatures were cooler, but it couldn’t spread further down the airway. The team identified that the Beaudette replicase gene, which is vital for viral replication, rendered it incapable of functioning at core temperature.

“This could be one of the reasons we didn’t see complete protection in our previous study”, Professor Lonneke Vervelde, lead collaborator at the Roslin Institute suggested. “We think that more heat resilience could result in higher levels of vaccine virus replication, which could prime the immune system and result in better protection”, Dr Bickerton added.

“It is also important to consider whether additional proteins need to be inserted into the Beaudette virus to create a more robust immune response. Together, these findings provide valuable information for IBV vaccine development, which could potentially apply to other coronaviruses too”, finished Dr Bickerton.

This research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

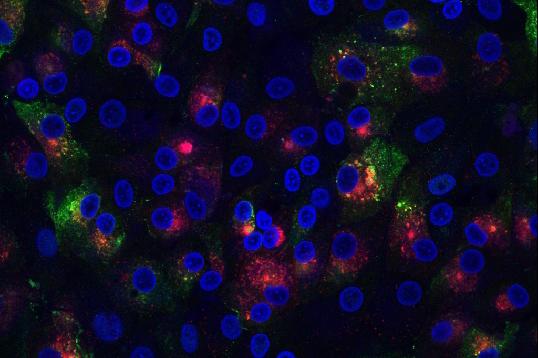

Image shows Beaudette infection in primary chicken kidney cell cultures.